Thoughts from the Misalignment Museum

Prompt

Pretend you are a designer and writer, and write a critical but fair review of your experience visiting the Misalignment Museum in San Francisco. Talk about some of the exhibits and your responses to them, as well as your experience speaking with the Museum’s creator. Then connect the existence of the Misalignment Museum to a larger discussion about art and creativity.

My Thoughts from the Misalignment Museum

Last weekend A couple months ago I got to visit the Misalignment Museum in San Francisco, a new pop up museum dedicated to demonstrating what emerging AI technology is capable of and sparking a conversation about where it’s taking us. I found the museum fascinating on a lot of levels, and I’ve been reflecting on it a lot since I visited, so I wanted to capture some of my thoughts here. First I’d like to talk about some of the exhibits, then talk about some new thoughts I’ve been having about AI and art since attending the museum.

These thoughts are of course mine and mine alone. No AI was harmed in the creation of this document.

The Exhibits

Spambots

Let’s start off with something easy! The Spambots is a cute little exhibit featuring a bunch of Spam Cans with arms typing an AI generated “narrative response” to Alduous Huxley’s Brave New World. But this version of Brave New World has had various nouns and verbs randomly replaced with pig alternatives (get it? Like spam).

As a reminder, Brave New World is a dystopian science fiction novel where individualized luxury and government mandated pleasure is used to placate the masses. It is also worth noting that though Brave New World is a pretty old book, it is not yet in the public domain. So I do wonder how the Huxley estate feels about this sort of thing.

Personally, when I look at the Spambots, I don’t think of Brave New World. I think of my [redacted family member], who recently wanted to send out a newsletter to update their clients on their [redacted business], and turned to AI to compose it. The resulting newsletter was serviceable…but written in that way most AI generated things are, where the prose was repetitive and lacked any sort of character. And ultimately it raised the crucial question, why was my [redacted family member] expecting their clients to read something that they hadn’t even bothered to write? To their credit, their response was that they didn’t expect any of their clients to actually read it. Which is a sorta farcical picture when you think about it. Just Spambots all the way down. Mindless text not actually being written for the placated masses to not actually read. Hmmm…now I am thinking of Brave New World after all.

The Palm Reader

The Palm Reader is the suggestion of a fortune telling booth, where if you place your hand into a kinda scary looking box an AI will analyze a picture of it and give you a fortune based off your palm’s lines.

Audrey, the museum’s creator and curator, told me that the intention of this exhibit was to respond to the wider cultural discussion about AI automation replacing various jobs. If palm reading is as much a science as an art, and fortunes can be consistently interpreted by real patterns in our palms, then it should be possible to replicate a human palm reader’s capabilities with a pattern recognizing AI. Audrey then mused about hiring a real human palm reader to work side by side with the AI one, so guests could compare and contrast their readings.

Oddly enough, this is one of the exhibits that didn’t really bother me on a gut emotional level, probably because in my mind the grift of palm reading is evenly matched by the grift of AI techno-optimism.

The LLM Timeline

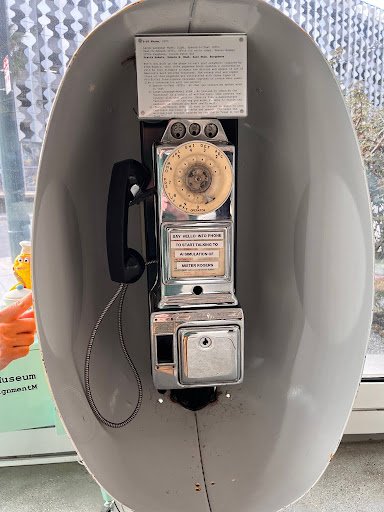

There were a series of exhibits that aimed to demonstrate the capabilities of LLMs (Learning Language Models). There was a vintage payphone that allowed you to “speak to Mr. Rogers”, meaning that when you picked up the phone you could have a conversation with an AI voice trained on recordings of Mr. Rogers. And then there was a “haunted” marionette that “stole” your voice, meaning when you read a poem into a microphone it quickly trained an AI voice to imitate the sound of yours.

Audrey explained to me how the Mr. Rogers Phone Booth is supposed to demonstrate the capability of AI voice replication to do good things like fulfill lifelong fantasies of having a meaningful conversation with a beloved figure who is no longer with us, while the Talking Marionette is supposed to demonstrate how AI voice replication can do bad things like put words in your mouth unconsensually. But I’m personally having trouble drawing the ethical line between these two exhibits. Does the Mr. Rogers Phone Booth not also demonstrate an AI replicated voice saying things Mr. Rogers never said without his permission? Why is it good when we do it to Mr. Rogers, but bad when we do it to ourselves? Is it the gratification of fantasy fulfillment that casts this in a positive light, and if so, what other kinds of fantasies are these AI technologies capable of helping us fulfull?

Would this exhibit be as well received if it had picked a different target and recreated the beloved voice of Robin Williams, someone who was famously adamant that his voice never be used to say things without his permission? One of his stipulations for performing in Aladdin was that his vocal performance as the Genie would never be used to sell anything…an agreement that Disney swiftly broke, leading to an extended falling out between Williams and Disney until the company finally issued an apology.

Or does the Misalignment Museum get a special pass from this line of questioning because the exhibits are being presented for demonstrative purposes?

Murphy the Talking Dog

This technically wasn’t an official exhibit at the Misalignment Museum, but it was actually the best exhibit at the Misalignment Museum.

Fun fact: Murphy’s legs were so short that if he was misbehaving he could be exiled by being placed on any moderately tall surface because he can’t jump down

Audrey had an adorable precious angel dog named Murphy who was trained to use those “speaking” buttons. On the floor there was an array of a couple large plastic buttons, and when Murphy pressed each button they said a different phrase. Things like “treat”, “mad”, “outside”, etc. This way Murphy could more directly communicate his thoughts to Audrey (and the rest of the museum). Or…could he?

We don’t know what Murphy the Dog is thinking. We don’t know how he thinks. His mind is a black box. To claim he’s communicating his thoughts with us is mere projection of my experience of what it’s like to use my brain to think onto Murphy’s doggy brain. Does Murphy know what a “treat” is? Does he know what “treat” means? Or does he know that pressing that particular button in that particular position usually leads to him getting a bit of food.

To prove the latter – at one point the array of buttons were accidentally rotated, and Murphy started spamming “mad” “mad” “mad”. Not because he was mad, but because the “mad” button was sitting where “treat” usually sat, and Murphy (as per usual) wanted a treat.

In this way, I think Murphy the “talking” dog is a perfect demonstration of how Learning Language Models function, and their inherent drawbacks. Namely, we cannot track the intent of Murphy’s mind. We cannot know if he comprehends language and the meaning of words the same way we do. We can only see his outputs.

If you are someone who’d be open to letting AI make decisions on your behalf, ask yourself this: would you trust Murphy the Dog to make decisions on your behalf?

The Impending Grimes Tapestries

I was lucky enough to be given a sneak peek of an upcoming flagship exhibit, two giant tapestries depicting AI images of cyber Marie Antoinette-esque figures “generated” “by” “Grimes”.

Marie Antionette After the Singularity

So let’s unpack that. But in order to do that, we need to have…

The Art Conversation

For me this exhibit raises the big question…is this art? Should we call “AI art”…art?

I’d like to start by making the proposition that the people who stand to benefit most from the general public accepting the byproduct of AI image generation tools as art, are also the people who have pushed for calling whatever those tools generate “art”. They could have called it “imagery”, “graphical output”, “sludge”, or any other phrase. (Though saying “come by my new children’s picture book where all the sludge was made using AI” doesn’t quite have the same ring to it). Calling it “art” was a choice, just like using the phrase “self driving” to describe whatever Tesla cars do of their own volition was a choice. These are decisions of branding. Should we (the public) play along and accept this choice, or guard our language and deny it?

Is this art? Did Grimes make an art? I’m not entirely sure, but my gut feeling is I’d prefer to think that she didn’t. So let’s examine that further…

Look, I’m not interested in gatekeeping art. That’s a total waste of time. But I am interested in celebrating craft. And I would go so far as to personally define art as the tangible or intangible byproduct of personal craft. Craft can be honed, craft can be developed. That’s why within “bad” art is always the potential for “good” art. The artist is always capable of improving their craft, and their art will reflect that improvement

I like framing this discussion around craft because I think craft covers an incredibly wide umbrella of skills, even those outside of the conventional category of art. Forklift driving is a craft. Working on an assembly line is a craft. Lawn mowing is a craft. Consider the saying “there is no such thing as unskilled labor” which has been circulating a lot lately. That’s because all labor is a kind of craft, and craft is built on skill.

So I think for me the big question within the bigger question is…is AI prompt writing a craft? Can you be good at prompt writing? Can you get better at it? And the answer is…maybe? A lot of the people who write a lot of AI prompts sure seem to think so, and I’m not about to discredit their experience.

I wonder…does the quality of the written prompt really have any bearing on the quality of the final output image out of context, or is it all in relation to the prompt writer’s internal expectations of what they wish to see generated? Would a prompt writer who is “better” than Grimes be able to generate a “better” image of Marie Antoinette After the Singularity, or just an image they personally like more? Hey, and while we’re at it…what makes images better than other images anyways…the skill involved in making them, just the vibes, or something else?

Here’s a hot take: you know what unequivocally isn’t craft? Consumption. Consuming media, consuming content, being a passive recipient…that’s not a craft. Craft is about contribution…contribution is the opposite of consumption.

I was passively fed this post by the Instagram Alogrithm that summed up this idea better than I ever could:

I like this joke, and now I’m going to ruin it by explaining my interpretation of it. There’s no such thing as a beginner song to listen to, because listening to songs isn’t a craft. The absurdity of this joke comes from the pretense that passively listening to songs could be a craft that can be honed and improved upon. But that isn’t the case, just like there’s no such thing as a beginner movie to watch, or a beginner flavor to taste, or a beginner story to be told, or a beginner image to generate. These are all acts of consumption, not contribution. And if we don’t call eating “cooking”, and we don’t call watching a movie “filmmaking”, and if we don’t call listening to music “songwriting”, then I don’t think we should accept calling AI generated images “art”.

But What If It Is?

Okay, now let’s take the above thought one step further.

There is of course a craft to reading any type of content critically…media literacy is definitely a craft, analysis and synthesis are crafts. Leting music enter your ears – not a craft. But making a playlist, DJing a setlist, using music to set a mood – that’s a craft. Letting food enter your mouth – not a craft. But cooking food, assembling a charcuterie board, determining flavor pairings – craft. Passively letting visuals and words enter your eyes – not a craft. But analyzing works of fiction, comparing and contrasting themes, compiling a summer reading list or a cinematic double feature – craft.

So here’s something I’ve been wondering…are there existing examples in the history of art that speak to the questions I’m raising about the merits of AI generated imagery? Surely we’ve had this conversation before. I’m not an art historian, I took one design history class in college and I like going art museums, but here’s my best stab at looking to the past to inform the present.

Two existing artists and their works who come to mind are Marcel Duchamp and his Readymades, and Sol LeWitt and his Wall Paintings. Duchamp took existing mass produced objects (most famously, a urinal) and presented them in a gallery art setting as if to say, “this was also made by human hands.” Why is a porcelain urinal less beautiful to us than a porcelain sculpture? They are both byproducts of tremendous craft. Meanwhile, Sol LeWitt is arguably the king of the prompt writers. He never picked up a single paintbrush or pencil in crafting his Wall Paintings. He just wrote the instructions for other people to follow. When talking about his work, he once explained, “…the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes the machine that makes the art.” That sounds very similar to me as the rhetoric used by prompt writers.

I think the precedent established by the works of these two artists raises a powerful rebuttal to my thoughts above. Or maybe they just exploit a clever loophole. Duchamp and LeWitt present works of art that are a byproduct of the craft of curation. And if curation is a craft, then is not all art just an act of endorsement? Traditionally an artist makes something themselves and then proclaims it to be art, (I used paint and brushes to make a piece of art) but the former doesn’t have to come before the latter. Anything is art if an artist dares to deem it so…and anyone can be an artist. Everyone already is an artist. So if I can pick up a rock from the ground and call it art, why can’t I pull an image from an AI image generator and call it art? I endorse it. This sludge has my seal of approval, I have curated it into my body of creative intent. That doesn’t mean it’s good, valuable, or that people have to be nice to me about it — I may even be tasked with defending my curatorial choices — but it is art and no one can take that away from me.

If there is any distinction to be drawn, it’s that AI art is a byproduct of the craft of curation, while nearly all other art is a byproduct of the craft of curation and at least one other specialized field. So if you still wish to separate AI art from the rest, you can filter by the underlying craft. This means that I do feel comfortable drawing the line that an AI generated image in the style of a digital painting isn’t really a Digital Painting, an AI generated image in the style of pixel art isn’t really Pixel Art, and an AI generated image in the style of a watercolor isn’t really a Watercolor, etc. They’re all lumped together under the mantle of “AI art”, regardless of their stylistic facade. I feel like as a general rule if we’re going to categorize works art then we should categorize them based on their production process, not the appearance of the final product.

But that’s assuming it’s worthwhile to categorize works of art at all. Which…it probably isn’t.

Back to Grimes

With all that pesky overthinking out of the way, the Misalignment Museum does something interesting with these AI generated images…something that I find irresistible. Audrey had these generated images woven into tapestries…which at first glance signifies a fuck-ton of craft. Look at all the strings! Look at all the deliberate human choices! If not made directly by human hands, then by some gigantic automated loom – which was made by human hands, and programmed by human minds. I don’t feel anything looking at the AI generated images, but I feel a sense of awe and appreciation looking at the threads it’s woven out of.

Just don’t let the medium massage the message…not this time. The tapestry could depict any image and I’d still be enthralled by it. I’m not enthralled by the image, I’m enthralled by the tapestry. Grimes didn’t do shit.

The Bigger Badder Stuff

The museum seemed to avoid highlighting any of the common conversational topics around AI that would call into question the ethics of this technology. Things like where is the data being sourced, who owns the original data, who owns the final content, is AI art really art, etc. I find this a little troubling and also a little telling, because at least in my experience, things that are ethically in the clear don’t shy away from their ethics being discussed. If the purpose of the Misalignment Museum is to spread awareness of AI technologies and spark new conversations, what does the museum stand to gain by faithfully documenting these technologies, but omitting the larger cultural conversations surrounding them?

AI as an act of Alienation

Here’s where I’m going to get both a little bit more out of my depth, and maybe a little bit more conspiratorial.

The way I see it, every process done in collaboration with an AI tool represents the robbery of an act of collaboration with a human being. If AI can research a topic with/for me, that means I don’t need to talk to other people about that topic. If AI can generate music with/for me, that means I don’t need to hit up one of my songwriting friends. Yes…the development process has been optimized, we’ve certainly cut out the middleman between myself and my goal of accomplishing a specific task…but maybe I wanted to hang out with the middleman, or maybe the middleman was going through some stuff and needed someone to talk to. We’re social creature, we’re wired to make things together. An AI tool can make me a wholly independent and fully optimized creative, but at what cost?

I have a very rudimentary understanding of Marx’s Theory of Alienation. But I think it’s appropriate to consider here. To put it very briefly, an alienated working class is a weakened working class. The less time people spend with other people, with ideas that aren’t their own, with art that challenges their view of the world…the more placatable and easily controllable they are. Ironically, a good example of this is the premise of Brave New World (sorry Spambots).

A lot of the AI technologies showcased at the Misalignment Museum seem to be specially geared to alienate us. We have voices that can be generated at the press of a button to placate our fantasies, images that can be generated to placate our imaginations, chatbots that will discuss any topic of our choosing – but on their terms. Will an AI chatbot explain to you how unfettered capitalism has lead to climate disaster, and oil companies have used misinformation campaigns to alienate and confuse the public? Probably not if Exxon is an investor.

Don’t Drink the Water

This was probably the most telling moment from my visit at the Misalignment Museum. About halfway through my time there, a group of Tech Bros showed up who all worked at various AI companies. They had heard about the Museum online and wanted to check it out for themselves. Audrey took them on a walking tour of the space, and eventually they got to the voice stealing marionette where another museum guest had her voice stolen as the Tech Bros watched. Audrey then asked if any of the Tech Bros wanted to try the demo, and I watched as one of the Bros actively recoiled from the microphone. None of them dared to try the demo.

Everyone is of course entitled to their privacy. But I did find it worrisome that the people working in the field on the backend were wary to interact with it on the frontend. It brought to mind the people who claimed the water in Flint Michigan was safe to drink, but never drank it themselves. After all, everyone is entitled to their privacy…not just the people responsible for the death of privacy.

Chat GPT’s Turn

For full thoroughness, I fed Chat GPT the same prompt I put at the top of this review, and here’s what it had to say.

Review: Navigating the Misalignment Museum of AI Technologies

As both a designer and writer, my interest in the intersection of technology and creativity led me to explore the Misalignment Museum in San Francisco. Promising an immersive journey through the capabilities of various AI tools, the museum beckoned with the allure of innovation and discovery. Here's a critical yet fair assessment of my experience navigating its exhibits.

Exhibits: Upon entering the museum, I was greeted by a dazzling array of AI-powered installations, each showcasing a different facet of artificial intelligence technology. One exhibit that immediately caught my attention was a interactive display demonstrating the potential of natural language processing algorithms. Visitors were invited to engage in conversation with an AI chatbot, which responded in real-time with startling accuracy and coherence.

Another compelling exhibit featured a deep learning model trained to generate artwork in the style of various renowned artists. As I observed the intricate brushstrokes and vibrant colors of these AI-generated masterpieces, I couldn't help but marvel at the ingenuity of the technology behind them. However, I found myself questioning the authenticity of the artistic expression, wondering if true creativity could be algorithmically replicated.

Conversation with the Creator: During my visit, I had the privilege of speaking with the museum's creator, Dr. Alicia Chen, a leading expert in AI research. Chen explained that the Misalignment Museum was conceived as a platform to showcase the capabilities and limitations of AI technologies in a creative context. She emphasized the importance of understanding the ethical implications of AI development and the need for responsible innovation in this rapidly evolving field.

In our conversation, Chen highlighted the concept of misalignment as a fundamental challenge in AI design. She discussed the inherent biases and limitations that can arise when training machine learning models on human-generated data, underscoring the importance of addressing these disparities to ensure fair and equitable AI systems.

Reflections: As I left the Misalignment Museum, I found myself grappling with the complexities of AI technology and its implications for society. While the exhibits demonstrated the remarkable capabilities of AI tools, they also raised important questions about the ethical considerations and potential pitfalls of relying too heavily on artificial intelligence.

Connection to Art and Creativity: The Misalignment Museum of AI Technologies serves as a thought-provoking exploration of the intersection between technology, art, and creativity. By showcasing the potential of AI to generate artwork, engage in natural language conversation, and perform other creative tasks, the museum challenges visitors to reconsider their preconceptions about the nature of creativity and the role of technology in shaping artistic expression.

In conclusion, while the Misalignment Museum offers a fascinating glimpse into the capabilities of AI technologies, it also serves as a reminder of the need for ethical oversight and responsible innovation in this rapidly advancing field. By engaging with these complex issues in a creative and thought-provoking manner, the museum encourages visitors to critically examine the impact of AI on society and the future of human creativity.